Truth and Memory

Associate specialist Masa Al-Kutoubi, on Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s experimental fictions

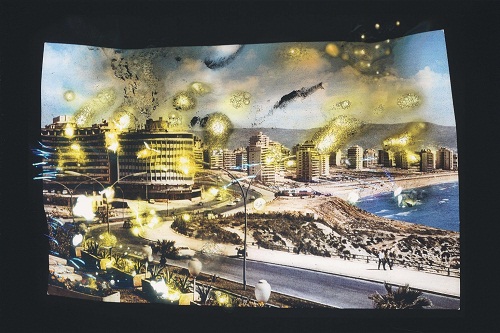

Pyromaniac Photograph (1998-2007), lambda print mounted on aluminum; © Christie’s Images

Lebanese duo Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige are perhaps best known as filmmakers (their 2008 film, Je Veux Voir, starred Catherine Deneuve and was nominated for best feature film at the Dubai International Film Festival). But their accomplishments as artists are just as impressive. True to their background, there’s a distinct cinematic feel to much of their art, explains Christie’s associate specialist of Modern and Contemporary Arab, Iranian & Turkish art, Masa Al-Kutoubi. Conceptual works like Wonder Beirut #22 (General View with Mountains), History of a Pyromaniac Photograph (1998-2007) blur the boundaries between truth and fiction, playing on the human instinct to believe whatever is seen. Here, Al-Kutoubi examines the piece in-depth, noting that truth and memory are often different things.

Nostalgia and myth

The work starts with an old image of a very affluent area in pre-civil war Beirut from about the 1960s. This kind of imagery is iconic because people are quite nostalgic today about how Beirut was before the civil war. They look at these old images and old postcards that show Beirut as being very Western — like the Monte Carlo of the Middle East — and they put the old Beirut on a pedestal when it wasn’t necessarily as great as they believe it was. For example, Lebanon was always positioned as the place where you can ski and swim in the same day, which is absolutely impossible. It’s part of the whole myth.

Faux history

The concept behind this work — number 22 in a series — relies on a story: Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige found these postcard negatives by a photographer named Abdallah Farah, who was commissioned by the Lebanese government after the civil war to take these nostalgic pictures. In the end, the photographer was so distraught by what was happening to his country that he burned the negatives. But the story is all fictional. In real life, you can still buy the original postcards on which these are based. But the pyromaniac photographer doesn’t exist.

Colorful destruction

Part of the effectiveness of this work, especially for Lebanese people, comes from seeing these familiar images shown in a completely different way. The artists oversaturated the colors — the image really pops out at you. The burning comes across very strongly. It invokes the destruction of a city that people were quite fond of — and very proud of. Visually, the burns are reminiscent of rocket explosions, and a lot of them are on buildings, which creates this impression that the buildings are on fire.

Cinematic truthiness

Joana and Khalil are originally film directors, so there’s a lot of cinematic sensitivity in their work. They are also very much inspired by Walid Raad and an artist group called the Atlas Group, whose work is entirely based on working on this idea of "fact-versus-fiction." Very similarly, they create these fake personas and scenarios, supporting them with visual "proof," as if they’re known facts, like history presentations. They demonstrate how people are willing to believe anything as long as they see it.

Lost history

Artists are really examining their histories in Lebanon right now. Schools don’t teach Lebanese history from the civil war onwards because it’s really hard to create a clear definition of what exactly happened. Everybody has his own version of what happened, often a version that’s politically driven.

Black border

The black border is part of the printed image, and the whole thing is mounted on aluminum. With this framing, it reminds me of a contact sheet, which is again a reference to what you would find in an photographer’s studio. They really want to push on this visual vocabulary of what you would find in a fictional character’s world. These scratches seem like they were really done by somebody who’s quite upset about what’s happening to his country.

Disneyland

In the late 1990s / early 2000s, the government started rebuilding a lot of the old districts that were basically reduced to rubble in the civil war. It rebuilt them to look exactly the way they did before the civil war — very shiny and new but in the style of the old buildings. There’s this weird old-versus-new, nostalgia thing again. But you can’t recreate the past. If you rebuild a building exactly the same way it looked in the ‘60s, it just looks like Disneyland. It’s like trying to forget that the civil war happened. But you can’t forget it.

Hadjithomas and Joreige’s Wonder Beirut #22 (General View with Mountains), History of a Pyromaniac Photograph is one of many works in Christie’s online-only auction of Modern and Contemporary Arab and Turkish art, running from Oct. 25 through Nov. 11.